Hidden Histories, Historical Marker Resource

Southern States Phosphate and Fertilizer Company

This Hidden History was created by SCAD student Jonah Song as part of his SCAD art history department coursework, with guidance from art history professor Holly Goldstein, Ph.D., 2025.

The Southern States Phosphate and Fertilizer Company: The Fertilizer Industry in the South historical marker was dedicated in 2022. View the Southern States Phosphate and Fertilizer Company historical marker listing.

Gallery

1. Necklace. Creative component. Courtesy of Jonah Song.

2. Necklace. Creative component. Courtesy of Jonah Song.

3. Necklace. Creative component. Courtesy of Jonah Song.

4. Necklace. Creative component. Courtesy of Jonah Song.

5. Pasture experiments from the Coastal Plain Experiment Station.

6. Georgia Coastal Plain Experiment Station.

7. Georgia Experiment Station cotton fertilization test.

8. Manipulated guano as precursor to chemical fertilizers.

9. Historical Advertisement for Phosphate Fertilizers.

10. Black dockworkers loading a Savannah phosphate schooner, 1906.

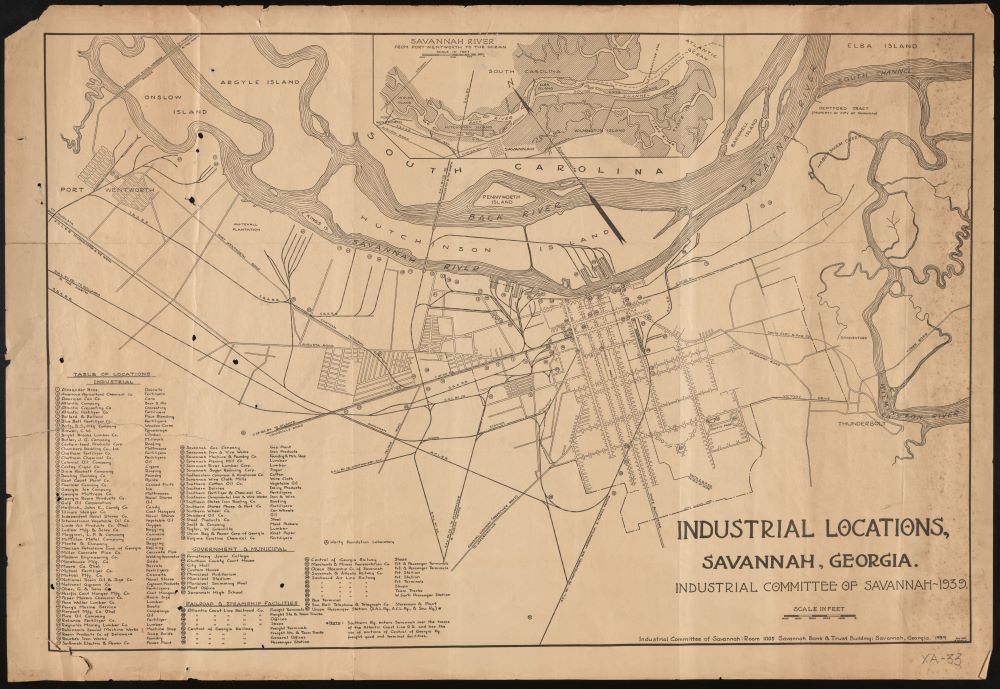

11. Map of the Industrial locations by the Industrial Committee of Savannah.

The GHS marker I selected is for the Southern States Phosphate and Fertilizer Company; the broader research topic I organized around this marker is on the chemical fertilizer industry in the South and how it both transformed and perpetuated economies of slavery.

I initially chose this marker because of my interest in gardening and biochemistry, and I believed it would connect well to the South’s agrarian roots and transitional Reconstruction economy. As I continued my research, I realized that I had somehow picked the perfect topic to align with my broader academic interests of American industrialization and capitalist development, racism as a tool of economic subjugation, generational trauma, and the physical scars of history.

These are topics I explore frequently through object centered research, namely making conceptual art jewelry pieces that synthesize historical and modern narratives. For this creative component I chose to use enamel as the primary medium because of its historical significance during the time period (1870s - 1900s) that chemical fertilizers were altering the Southern landscape – broader American industrialization made enamelware a popular consumer good at the time.

I chose copper as the base metal because of its affordability and beautiful golden color after firing with Thompson’s 2015 “Warm Flux” enamel. First, I used a floor shear to cut a square foot of copper sheet into smaller rectangular strips; then I embossed these strips with a steel pattern plate to create a raised topographical texture. This metal “topography” represents the physical, agricultural impact of phosphate fertilizer on Southern lands. Next, I used a jeweler’s saw to cut and pierce ten chain links, a pendant, and a frame out of the copper; I then used a rawhide mallet to form each piece into a slight dome. After checking the size and layout of the copper pieces, I prepared them for enameling by sanding and filing any rough edges left by the sawblade and cleaning them in a solution of sodium bisulfate (pickle).

Finally, each copper piece is ready to be enameled - a process of fusing different colors of powdered glass at high temperatures (1400 - 1500 degrees Fahrenheit) to metal forms. Glass is sifted, wet-packed, or painted onto the metal in powder form; the metal is then placed on a steel firing trivet and is fired in a kiln for 1 - 3 minutes. Each piece is then allowed to cool, which reveals the true color of the enamel, and is then re-pickled or washed with clean water to remove excess firescale. Any unwanted glass particles fused to the surface or uneven glass layers are then ground under running water with an alundum stone or diamond files to create a smooth, even surface before the next layer of enamel is applied. This entire process is repeated multiple times to build up layers of color, as each “color” is a separate glass powder.

I first applied a base and counter coat to each chain link (22 coats total) in 2015 Warm Flux, a transparent gold-bearing enamel, to draw out the metal oxides into the glass and create a brilliant golden base hue for the actual color application. The back of the pendant frame was counter enameled twice, and the main pendant itself was counter enameled once. In total, I applied and kiln-fired 25 initial coats of enamel.

Next, I began applying the actual color coats onto each copper piece. The two largest chain links were enameled 6 times; the four second-largest chain links were enameled 10 times; the frame was enameled 3 times; the pendant was enameled 3 times; the four smallest links were enameled 8 times. In total, I fired 30 color coats of enamel for a total of 55 layers of enamel.

The 3-dimensional white pendant symbolizes phosphate fertilizers (phosphate is a powdery white rock) and how they projected the South forward from the flat, 2 dimensional mottled black and red frame (symbolizing the social and environmental traumas of plantation slavery and the destruction of the Civil War). The bony, almost vertebrae-like design of the pendant reflects how agriculture was the literal backbone of the Southern economy, and its organic lines contrast the rigid, geometric structure of the pendant’s frame. This highlights how phosphate fertilizers were a naturally occurring, locally derived solution to soil depletion, whereas guano was an imported foreign good that operated through regimented trade networks. However, the white of the pendant isn’t pristine - it’s filled with swirling reds, greens, and oranges to represent that phosphate-supported agriculture was never a true step away from plantation slavery.

The enamel colors - and the graduated size of the chain links - add further narrative depth to the piece. The largest chain links, which are closest to the pendant, are in shades of black and red that almost completely obscure the brilliant golden base. As the chain links shrink away from the center of the necklace, more of the golden basecoat becomes visible and the bloody red splotches fade to verdant green and blooming flowers. This visual transition represents the shrinking amount of fertile land before the introduction of phosphate fertilizers and that only time and distance can truly heal the wounds of the past.

Finally, to connect the links I cut a plain white cotton T-shirt into strips and braided and knotted the enameled pieces together. The choice of material reflects that cotton capitalism is still well and alive today; when we buy cheap T shirts made in China or made in Nepal, we rarely ever stop to think about where the cotton came from, who harvested and processed it, where the fibers were woven into fabric, or how the fabric became a T-shirt which we then purchased. The intricate braids and knots symbolize how the story of phosphate fertilizers are literally woven into the fabric of Southern history. Notably, however, the center pendant is left relatively unobscured by fabric, allowing the wearer’s skin to shine through the intricately hand pierced negative space. This emphasizes that phosphate fertilizers didn’t benefit everyone equally: the color of your skin directly influenced whether you would profit from or be subjugated by newly emerging phosphate industries.

Lastly, the final knot – the “clasp” of the necklace – is left undone. I invite the wearer to contribute their own “knot”, such as a hair tie, rubber band, claw clip, etc. to finish the piece and tie it around their neck. This forces us to take accountability for our own role as consumers of mass-produced clothing and how our purchasing decisions can reinforce or subvert global extractive economies.

Alabama Cooperative Extension System. “Phosphorus Basics: Understanding Phosphorus Forms and Their Cycling in the Soil - Alabama Cooperative Extension System,” April 24, 2025.

https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/crop-production/understanding-phosphorus-forms-and-their-cycling-in-the-soil/

Averitt, Jack N. Georgia’s Coastal Plain. Vol. 2. Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1964.

Cohen, William. “Negro Involuntary Servitude in the South, 1865-1940: A Preliminary Analysis.” The Journal of Southern History 42, no. 1 (1976): 31–60.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2205660.

College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Photograph Collection, UA0004. University of Georgia Archives, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

“Cotton Fertilization Experiments.” Georgia Historical Society. Georgia Experiment Station, 1920.

Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher. Loading a phosphate schooner, Savannah, Ga. Georgia Savannah United States, None [Between 1900 and 1906] Photograph.

https://www.loc.gov/item/2016803977/.

Fleischman, Richard, Thomas Tyson, and David Oldroyd. “THE U.S. FREEDMEN’S BUREAU IN POST-CIVIL WAR RECONSTRUCTION.” The Accounting Historians Journal 41, no. 2 (2014): 75–109.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43487011.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988)

Fox, Adam. “The Role of Phosphorus in Plant Growth and Productivity | IFA’s Blog.” Helping to Grow (blog), January 9, 2024.

https://grow.ifa.coop/agronomy/phosphorus-role-in-plant-growth-productivity

Georgia Historical Society. Southern States Phosphate and Fertilizer Company. Georgia Historical Marker. Accessed May 17, 2025.

https://www.georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/southern-states-phosphate-and-fertilizer-company/.

G. Ober & Sons Co. “The First Mixed Fertilizer in America: A Pamphlet Printed in 1859, Reproduced by G. Ober & Sons CO.” Georgia Historical Society, 1936.

"Hardee's Cotton Boll Fabric Poster." Object. Savannah: c1880. From Georgia Historical Society: GHS 2203-AF-001, N. A. Hardee's Son and Co. records.

Johnson, Walter. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Harvard University Press, 2013.

https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjsf5q7.

Map of the industrial locations by the Industrial Committee of Savannah. 1939. Digital Library of

Georgia.

https://dlg.usg.edu/record/gsg_edgm_edgm-xa-033#item.

Rutherford, Mildred Lewis. King Cotton: The True History of Cotton and the Cotton Gin, 1922. Preserved pamphlet accessed through the Georgia Historical Society.

Sawers, Brian. “Property Law as Labor Control in the Postbellum South.” Law and History Review 33, no. 2 (2015): 351–76.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/43670779.

Shick, Tom W., and Don H. Doyle. “The South Carolina Phosphate Boom and the Stillbirth of the New South, 1867-1920.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 86, no. 1 (1985): 1–31.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27567881.

Stoll, Steven. Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America. Macmillan, 2003.

Weiman, David F. “The Economic Emancipation of the Non-Slaveholding Class: Upcountry Farmers in the Georgia Cotton Economy.” The Journal of Economic History 45, no. 1 (1985): 71–93.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2122008.

Wells, Jonathan. Capitalists Without Capital: The Burden of Slavery and the Impact of Emancipation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).